Shutterstock

Shutterstock

Amid the coronavirus pandemic we are being warned of a “second wave” of mental health problems that threatens to overrun an already weakened mental health service.

As we emerge from this crisis, while some people may need specialist help with treating mental illness, everybody can benefit from strategies to improve mental health.

This is because mental health is more than just the absence of mental illness. Positive mental health is a combination of feeling good and functioning well.

Mental illness vs mental health: what’s the difference?

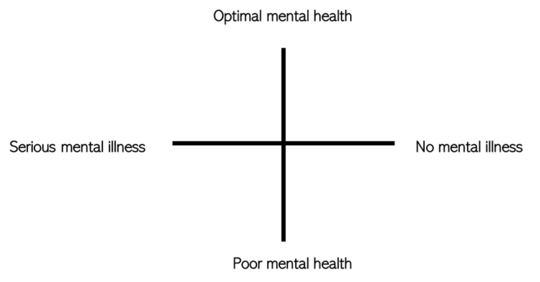

Mental health and mental illness are not simply two sides of the same coin. Mental health, just like physical health, exists on a spectrum from poor to optimal.

Get The Latest By Email

With physical health, some days we naturally feel stronger and more energetic than others. Similarly, some days our mental health is worse than others, and that too is a natural part of being human. We may feel tired, grumpy, sad, angry, anxious, depressed, stressed, or even happy at any point in time. These are all normal human emotions, and aren’t on their own a sign of mental illness.

Someone living with a mental illness can be experiencing optimal mental health at any point in time, while someone else can feel sad or low even in the absence of a mental illness.

Differentiating between poor mental health and symptoms of a mental illness is not always clear-cut. When poor mental health has a sustained negative impact on someone’s ability to work, have meaningful relationships, and fulfil day-to-day tasks, it could be a sign of mental illness requiring treatment.

Mental health and mental illness are not the same thing. You can have poor mental health in the absence of a mental illness. Supplied, adapted from Keyes 2002.

Mental health and mental illness are not the same thing. You can have poor mental health in the absence of a mental illness. Supplied, adapted from Keyes 2002.

What does positive mental health look like?

Mental health is more than just the absence of mental illness.

Positive mental health and well-being is a combination of feeling good and functioning well. Important components include:

-

experiencing positive emotions: happiness, joy, pride, satisfaction, and love

-

having positive relationships: people you care for, and who care for you

-

feeling engaged with life

-

meaning and purpose: feeling your life is valuable and worthwhile

-

a sense of accomplishment: doing things that give you a sense of achievement or competence

-

emotional stability: feeling calm and able to manage emotions

-

resilience: the ability to cope with the stresses of daily life

-

optimism: feeling positive about your life and future

-

self-esteem: feeling positive about yourself

-

vitality: feeling energetic.

How can I cultivate my mental health?

Your mental health is shaped by social, economic, genetic and environmental conditions. To improve mental health within society at large, we need to address the social determinants of poor mental health, including poverty, economic insecurity, unemployment, low education, social disadvantage, homelessness and social isolation.

Positive mental health involves being able to cope with the challenges of daily life. Shutterstock

Positive mental health involves being able to cope with the challenges of daily life. Shutterstock

On an individual level, there are steps you can take to optimise your mental health. The first step is identifying your existing support networks and the coping strategies that you’ve used in the past.

There are also small things you can do to improve your mental health and help you to cope in tough times, such as:

-

helping others

-

finding a type of exercise or physical activity you enjoy (like yoga)

-

connecting with others, building and maintaining positive relationships

-

learning strategies to manage stress

-

having realistic expectations (no one is happy and positive all the time)

-

learning ways to relax (such as meditation)

-

counteracting negative or overcritical thinking

-

doing things you enjoy and that give you a sense of accomplishment.

How do I know if I need extra support?

Regardless of whether you are experiencing a mental illness, everyone has the right to optimal mental health. The suggestions above can help everyone improve their mental health and well-being, and help is available if you’re not sure how to get started.

However, when distress or poor mental health is interfering with our daily life, work, study or relationships, these suggestions may not be enough by themselves and additional, individualised treatment may be needed.

If the answer to RUOK? is no, or you or your loved ones need help, reaching out to your local GP is an important step. If you are eligible, your GP can refer you for free or low-cost sessions with a psychologist, exercise physiologist, dietitian, or other allied health or medical support services.

About The Author

Simon Rosenbaum, Associate professor & Scientia Fellow, UNSW and Jill Newby, Associate Professor and MRFF Career Development Fellow, UNSW

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

books_health