Legumes are the least well known source of fibre, but they may be the most important for human health. Dey/Flickr

Legumes are the least well known source of fibre, but they may be the most important for human health. Dey/Flickr

Six out of ten Australians don’t eat enough fibre, and even more don’t get the right combination of fibres.

Eating dietary fibre - food components (mostly derived from plants) that resist human digestive enzymes - is associated with improved digestive health. High fibre intakes have also been linked to reduced risk of several serious chronic diseases, including bowel cancer.

In Australia, we have a fibre paradox: even though our average fibre consumption has increased over the last 20 years and is much higher than in the United States and the United Kingdom, our bowel cancer rates haven’t dropped.

This is probably because we’re eating a lot of insoluble fibre (also known as roughage) rather than a combination of fibres that includes fermentable fibres, which are important for gut health.

Get The Latest By Email

The different types of fibre

Eating a combination of different fibres addresses different health needs. The NHMRC recommends adults eat between 25 and 30 grams of dietary fibre each day.

For convenience, dietary fibre can be broadly divided into types:

-

Insoluble fibres or roughage promote regular bowel movements. Sources of insoluble fibre include wheat bran and high-fibre cereals, brown rice, and wholemeal breads.

-

Soluble fibres slow digestion, lower plasma cholesterol levels, and even out glucose uptake to the blood. Sources of soluble fibre include oats, barley, fruits, and vegetables.

-

Resistant starches contribute to health by feeding good bacteria in the large bowel, which improves its function and reduces risk of disease. Sources of resistant starch include legumes (lentils and beans), cold cooked potatoes or pasta, firm bananas, and whole grains.

Vegetables provide a form of soluble fibre. Felipe Ortega

Vegetables provide a form of soluble fibre. Felipe Ortega

Resistant starch

Resistant starches are perhaps the least well known of the different types of fibre, but they may be the most important for human health.

International studies find a stronger association with reduced bowel cancer risk for starch consumption than total dietary fibre.

Resistant starch provides a likely mechanism for this association because it promotes gut health through the short-chain fatty acids produced by good bacteria. The short-chain fatty acid butyrate is the preferred energy source for cells that line the large bowel.

If we don’t eat enough resistant starch, these good bacteria in our large bowel get hungry and feed on other things including protein, releasing potentially damaging products such as phenols (digestion products of aromatic amino acids) instead of beneficial short-chain fatty acids.

Eating more resistant starch protects the bowel from the damage associated with having a hungry microbiome. It can also prevent DNA-damage to colon cells; such damage is a prerequisite for bowel cancer.

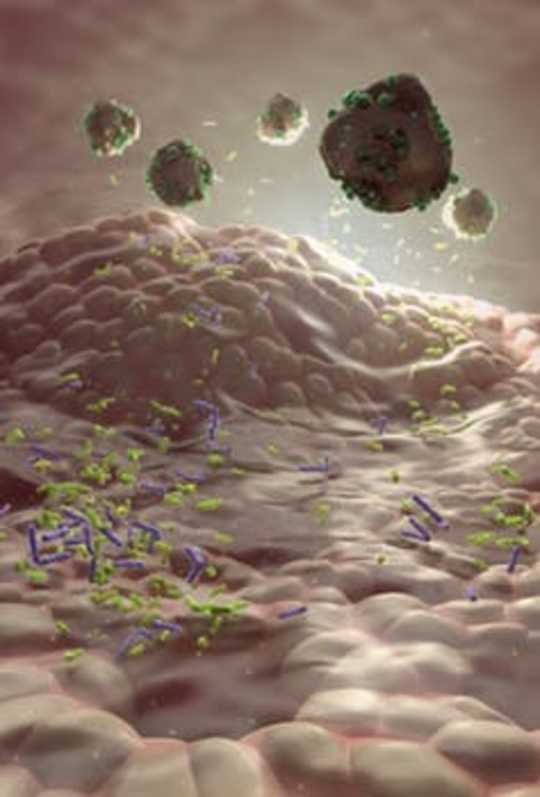

Resistant starch feeds good bacteria in the large bowel. Chris Hammang

Resistant starch feeds good bacteria in the large bowel. Chris Hammang

Consuming at least 20 grams a day of resistant starch is thought to promote optimal bowel health. This is almost four times more than a typical western diet provides; it’s the equivalent to eating three cups of cooked lentils.

In the Australian diet, resistant starch comes mostly from legumes (beans), whole grains, and sometimes from cooked and cooled starches in dishes such as potato salad.

This is in stark contrast with other societies, such as India where legumes are a significant part of the diet, or South Africa where maize porridge is a staple often eaten cold.

Cooling starches allows the long chains of sugars that make them up to cross-link, which makes them resistant to digestion in the small intestine. This, in turn, makes them available to good bacteria in the large bowel.

Digestive health

A healthy digestive system is critical for good health, and fibre promotes digestive health. While most of us feel uncomfortable talking about our bowel movements, having an understanding of what is optimal in this department can help you adjust the amount of fibre in your diet.

There’s a wide array of bowel habits in the normal population, but many health experts agree that using tools such as the Bristol stool chart can help people understand what bowel movements are best. As usual with medical advice, if you’re concerned you should start a conversation with your doctor.

A high-fibre diet should give you a score of four or five on the Bristol stool chart, and less than four could indicate that you need more fibre in your diet. If you increase your fibre intake, you will also need to drink more fluids because fibre absorbs water.

But gut health is not as simple as just ensuring regular bowel motions. Australians are, on average, eating sufficient insoluble fibre, but not enough resistant starch, which promotes gut health by feeding good bacteria in the large bowel.

Eating a combination of dietary fibres is imperative for digestive health. Chris Hammang

Eating a combination of dietary fibres is imperative for digestive health. Chris Hammang

Resistant starches are fermentable carbohydrates, so you might wonder if eating more of them will increase flatulence. Farting is normal and the average number of emissions per day is twelve for men and seven for women, although that varies for both sexes from two to 30 emissions.

Nutritional trials have shown high-fibre intakes of up to 40 grams daily, including fermentable carbohydrates, don’t lead to significant differences in bloating, gas or discomfort, as measured by the Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index.

Nonetheless, it’s sensible to increase your fibre intake over weeks and drink adequate water. You might change to a high-fibre breakfast cereal one week, change to a wholegrain bread the next, and gradually introduce more legumes over several weeks.

A slow increase will allow you and your good bacteria to adjust to the high-fibre diet, so that you aren’t surprised by changes in your bowel habits. The composition of bacteria in your large bowel will adjust to suit a high-fibre diet, and over weeks these changes will help you process more fibre.

Getting enough fibre is important, but getting a combination of fibre is imperative for good digestive health.

Most people know that eating insoluble fibre improves regular bowel movements, but the benefits of soluble fibre in slowing glucose release and resistant starch in promoting beneficial bacteria are less well known. Including a variety of fibres in your diet will ensure you get the health benefits of all of them.![]()

About The Author

David Topping, Chief Research Scientist, CSIRO; Arwen Cross, Science Communicator, CSIRO, and Christopher Hammang, Biomedical Animator, CSIRO

books_food

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.