Some research suggests the luteal phase may be optimal for weight lifting. SeventyFour/ Shutterstock

If you’re someone who has to deal with a period regularly, you’re probably all too familiar with just how much your energy levels can change throughout your cycle thanks to hormonal fluctuations. Not only can this sometimes make even the simplest daily tasks challenging, it can make it even harder to stay motivated to keep fit and stick to your regular workout routine, especially when noticing a decline in your performance.

Your cycle

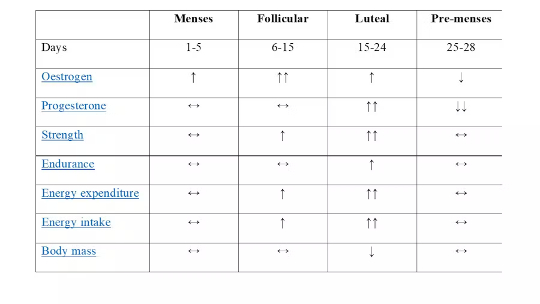

The menstrual cycle can be split into four phases: menses, follicular, luteal and pre-menses. The concentration of the sex hormones oestrogen and progesterone change in each phase.

During the menses phase (your period), oestrogen and progesterone are at their lowest levels. But as you move into the follicular phase, oestrogen begins to increase. In the luteal phase, which immediately follows, progesterone concentrations also begins to increase. Both hormones reach their peak near the end of the luteal phase, before dropping dramatically during the pre-menstrual phase (days 25-28 of the average cycle). Hormone concentrations change in each phase on your cycle. Dan Gordon, Author provided

Hormone concentrations change in each phase on your cycle. Dan Gordon, Author provided

Research shows that thanks to these hormones, certain phases of your menstrual cycle are optimised for different types of exercise.

Get The Latest By Email

For instance, the luteal phase may be the perfect time for strength training thanks to the boost in both oestrogen and progesterone. Research shows there are noticeable increases in strength and endurance during this phase. Energy expenditure (calories burned) and energy intake are also greater during the luteal phase, alongside a slight decrease in body mass. You may also find you feel more energetic and capable of exercise during this phase. The hormone concentrations in the luteal phase may also promote the greatest degree of muscle change.

The folicular phase also shows some increases in strength, energy expenditure and energy intake – albeit smaller.

But when progesterone and oestrogen are at their lowest levels during your period (menses phase), you’re likely to see fewer changes when it comes to building muscle. There’s also a greater chance that you will feel fatigued due to low hormone levels, alongside the loss of menstrual blood. This may be a good time to consider adjusting your training, focusing on lower-intensity exercises (such as yoga) and prioritising your recovery.

So based on the way hormones change during each phase of the menstrual cycle, if you’re looking to improve strength and fitness you may well want to plan your most intense workouts for the follicular and luteal phases to achieve the greatest gains.

Too good to be true?

This all seems fantastic, and you may well be wondering why more women are not following this trend. But the answer is that it may all be too good to be true.

While the responses reported do take place, actually putting this all into practice is easier said than done. First, most research on the menstrual cycle’s impact on fitness assume the cycle has a regular pattern of 28 days. But 46% of women have cycle lengths that fluctuate by around seven days – with a further 20% exhibiting fluctuations of up to 14 days. This means a regular cycle varies for each person.

The second key assumption is that the responses of progesterone and oestrogen, which drive the changes in fitness are constant. But this is often not the case, as both oestrogen and progesterone exhibit large variations both between cycles and each person. Some women may also lack oestrogen and progesterone due to certain health conditions. These responses make it difficult to track the phases of the cycle precisely through monitoring of hormones alone – and make syncing accurately also very difficult.

So while the idea of syncing your menstrual cycle with your workouts seems logical, the outcomes each person sees are likely to vary. But if you do want to give it a try, menstrual tracking apps – alongside the use of ovulation test strips and temperature monitoring – can help give you a good idea of what stage in your menstrual cycle you’re at.![]()

About The Author

Dan Gordon, Associate Professor: Cardiorespiratory Exercise Physiology, Anglia Ruskin University; Chloe French, PhD Candidate in Sport and Exercise Science, Anglia Ruskin University, and Jonathan Melville, PhD Candidate in Sport and Exercise Science, Anglia Ruskin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

books_fitness