The global death toll from COVID-19 has now passed a million. To slow the spread of the disease, we need to better understand why some places have higher numbers of cases and deaths than others.

One factor that could partially explain this is air pollution. Research has shown that long term exposure to pollutants such as fine particulate matter (often called PM2.5, as these are particles smaller than 2.5 micrometres), nitrogen dioxide (NO₂) and sulphur dioxide (SO₂) can reduce lung function and cause respiratory illness. These pollutants have also been shown to cause a persistent inflammatory response even in the relatively young and to increase the risk of infection by viruses that target the respiratory tract.

The pathogen that causes COVID-19 – SARS-CoV-2 – is one such virus. Several studies have already suggested that poor air quality can leave people at greater risk of contracting the virus, and at greater risk of serious illness and death. A study of the US found that even a small increase in PM2.5 concentrations of 1 microgram per cubic metre is associated with an 8% increase in the COVID-19 death rate. Our new research looked at the relationship between COVID-19 cases and exposure to air pollution in the Netherlands and found that the equivalent figure for that country could be up to 16.6%.

The unusual case of the Netherlands

After analysing data for 355 Dutch municipalities, we found that an increase in fine particulate matter concentrations of 1 microgram per cubic metre was linked with an increase of up to 15 COVID-19 cases, four hospital admissions and three deaths.

Get The Latest By Email

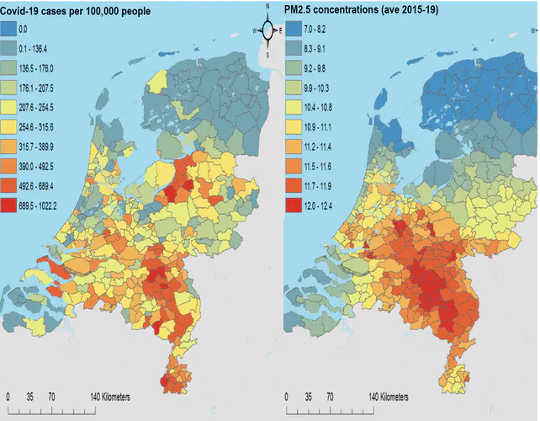

The first confirmed COVID-19 case in the Netherlands occurred in late February and by late June over 50,000 cases had been identified. The national spread of COVID-19 cases shows a greater number in the south-eastern regions.

COVID-19 cases per 100,000 people and annual concentrations of PM2.5 (averaged over the period 2015-19) in the Netherlands. Matt Cole, Author provided

COVID-19 cases per 100,000 people and annual concentrations of PM2.5 (averaged over the period 2015-19) in the Netherlands. Matt Cole, Author provided

Unusually, these hotspots of disease transmission are in relatively rural regions where there are fewer people living close together. The Dutch media offered one potential explanation. In late February and early March each year, these areas hold carnival celebrations which attract thousands of people to street parties and parades – 2020 was no exception, so does that explain the rapid spread of COVID-19 there?

While it’s likely that the carnival celebrations played a role, the pattern of cases across these regions suggest other factors may be at least as important.

The south-eastern provinces of North Brabant and Limburg house over 63% of the country’s 12 million pigs and 42% of its 101 million chickens. Intensive livestock production produces large amounts of ammonia. These particles often form a significant proportion of fine particulate matter in air pollution. Concentrations of this are at their highest in air samples from the south-east of the Netherlands.

The correlation between these indicators of air pollution and cases of COVID-19 is clear to see, but is it just a coincidence?

Pollutants associated with COVID-19

Our analysis used COVID-19 data up to June 5 2020, capturing almost the entire known course of the Dutch epidemic. The relationship we found between pollution and COVID-19 exists even after controlling for other contributing factors, such as the carnival, age, health, income, population density and others.

To put our results in context, the highest annual average concentration of fine particulate matter in a Dutch municipality is 12.3 micrograms per cubic metre, while the lowest is 6.9. If concentrations in the most polluted municipality fell to the level of the least polluted, our results suggest this would lead to 82 fewer disease cases, 24 fewer hospital admissions and 19 fewer deaths, purely as a result of the change in pollution.

The correlation we found between exposure to air pollution and COVID-19 is not simply a result of disease cases being clustered in large cities where pollution may be higher. After all, COVID-19 hotspots in the Netherlands were in relatively rural regions. Still, region-level data can only get us so far. Within regions, pollution levels and COVID-19 cases can vary considerably from place to place, making it hard to estimate the precise relationship between the two.

Being able to study this link among individual people would allow us to more precisely eliminate the influence of age and health conditions. But until this kind of data is available, the evidence of a relationship between pollution and COVID-19 can never be conclusive.

About the Authors

Matt Cole, Professor of Environmental Economics, University of Birmingham; Ceren Ozgen, Assistant Professor in Economics, University of Birmingham, and Eric Strobl, Professor of Economics, Université de Berne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

books_environmental