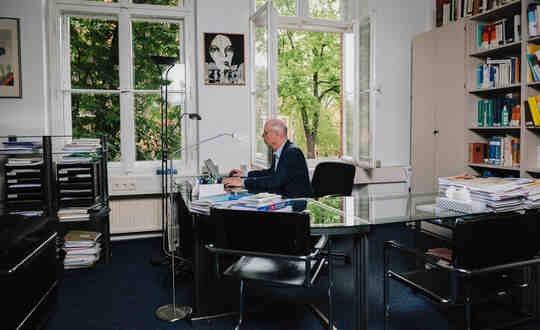

German sexologist Klaus Beier works in his office at the Institute of Sexology and Sexual Medicine at Charité, a university hospital in Berlin. In 2005, Beier founded Prevention Project Dunkelfeld, which aims to treat pedophilia with therapy and medication. The experiment hinges on a risky proposition: not reporting those who have offended.

Klaus Beier is the archetypal German sexologist. Terse, bald, and, during a Zoom call last fall, wearing a blue blazer and clear-rimmed eyeglasses, he exudes annoyance at questions about his work with pedophiles — which, he suggests, is now widely accepted in his country, and is supported by politicians and major philanthropies. Beier heads an institute at one of Europe’s biggest university hospitals and has appeared on numerous national talk shows. In 2017, he was even awarded the Order of Merit, Germany’s equivalent of the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Nearly everywhere outside Germany, however, what Beier has been doing for more than 15 years would be not just controversial but illegal. He founded and directs Prevention Project Dunkelfeld, arguably the world’s most radical social experiment in treating pedophilia. The experiment hinges on a risky proposition: not reporting those who have offended. Instead, Beier and his team promote prevention, rather than punishment, by encouraging people who are sexually attracted to children and adolescents to come forward to receive therapy and medication instead of acting on their urges or going untreated by health professionals. Dunkelfeld guarantees all patients anonymity and free outpatient treatment. After completing the one-year program, patients receive follow-up treatment, never having to interact with the justice system. Since 2005, Beier says, thousands have reached out to take up the offer.

These men — they are almost all men — admit they fantasize about committing criminal acts that repulse and horrify most people. Many doctors find it difficult to empathize with such patients, but not Beier. “I would never judge anyone for their fantasies,” he says.

Get The Latest By Email

But some of the men that Dunkelfeld treats admit to more than just fantasies. They confide to having already acted on their impulses — that is, to raping children or viewing child pornography. Here, Dunkelfeld draws a line: If a patient says he plans to abuse a child while he is in treatment, the center will work with them on preventative measures, contacting the authorities only as a last resort. If a patient admits to an incident that happened in the past, however, the center will not report it. This is possible because, unlike most countries, Germany doesn’t have a law mandating professionals to report child abuse that has occurred in the past or might occur in the future.

Germany’s public health insurance system has supported Dunkelfeld since 2018. The health ministry provides the program with some $6 million per year and Beier says interest in the program’s model is growing worldwide. “I’m confident we’ll be able to establish our ideas in other countries,” he says.

It won’t be easy, at least in the United States, which has especially stringent reporting laws designed to ensure that authorities learn about — and prosecute — child sexual abuse. These laws are meant to deter anyone from ignoring or covering up crimes against children. Such mandatory reporting laws are found in nearly every state and U.S. territory, and impose penalties from fines to imprisonment for those who fail to report.

Despite these longstanding efforts, nearly 61,000 children are sexually abused annually in the U.S., according to the Department of Health & Human Services. With such abuse often going unreported, the real count may be even higher, suggesting a clear need for better approaches to the problem. This has some U.S. experts eager to explore ways to apply the preventative approach without skirting mandatory reporting laws. In March, the Moore Center for the Prevention of Child Sexual Abuse at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health — a research hub for child sexual abuse prevention and an advocacy center for legislation and funding for preventative approaches — received a $10.3 million grant for a new initiative to develop and circulate efforts to prevent perpetrators from abusing children. The sum, awarded by Oak Foundation — a Switzerland-based foundation focused on addressing “issues of global, social, and environmental concern” — is thought to be the highest yet invested in the U.S. in preventative efforts.

Not everyone is convinced that Dunkelfeld holds the answers, however. Critics say Beier’s claims of success are based on evidence that is weak or overstated — or even, some argue, nonexistent. More pressing are the issues surrounding normalizing pedophiles and reporting offenders. And even if the program works, the removal of the one crucial guardrail that makes Dunkelfeld most different — mandatory reporting — may prove impossible in most places outside Germany. (Beier says professionals from more than 15 countries have contacted Dunkelfeld for advice and training, but programs must operate within the confines of their respective mandatory reporting laws. Patients who receive treatment from Don’t Offend India, for example, are informed about the legal consequences of revealing past offenses.)

Still, others argue that, given the large number of children at risk of abuse, Dunkelfeld’s concept can’t be dismissed out of hand. “The concept makes a whole lot of sense,” says Fred Berlin, director of the National Institute for the Study, Prevention, and Treatment of Sexual Trauma in Baltimore.

“It’s an opportunity,” he adds, “for people who want help to get it.”

Beier was born in Germany’s capital at the height of the Cold War, in 1961. “I am a Berliner,” he says, smiling at his invocation of President John F. Kennedy’s famous use of the phrase in a 1963 speech. His formative years were spent in “Wirtschaftswunder,” the period of “economic miracle” in West Germany following World War II. Underwritten by American troops and the nuclear umbrella, this era helped Germany rebuild into a country with functioning public institutions, comparatively high levels of social trust, and a robust health care system — a backdrop that would inform his work.

In graduate school in the 1980s, Beier’s studies gravitated toward abnormal behaviors and mental problems, known as psychopathology. Sexology in particular fascinated him, he says, because doing it well requires incorporating biology, psychology, and the science of culture.

After graduating, Beier spent decades at different university hospitals in Germany, working with men attracted to children. His clinical work convinced him that pedophilia is a lifelong sexual orientation that usually begins in adolescence. “Most people would be very happy to change,” Beier says. He worked with men who confided that they had committed horrific acts of child abuse — but who had never been caught by police. Because of uniquely strong German patient-doctor confidentiality laws, Beier says, he was obliged to keep their secrets.

Beier’s interviews with these men inspired Project Dunkelfeld — a German term meaning “dark field,” referring to the men who have committed crimes but who haven’t been detected by law enforcement. In late 2003, he submitted a proposal for a pilot project to the Volkswagen Foundation, an independent organization that was originally affiliated with the car company but is now one of the largest philanthropies in Europe. Even in Germany, Beier knew, the idea of a prominent established institution funding a program supporting pedophiles was a longshot.

But the foundation, he says, granted the project more than $700,000 for three years. “I was very surprised,” Beier says. Even more surprising, he says, was that soon after, one of Europe’s biggest advertising companies, Scholz & Friends, created advertisements for Dunkelfeld for free. For up to eight weeks, posters for the project appeared across Germany in bus stops, newspapers, and on television — 2,000 spots in all. “You are not guilty because of your sexual desire, but you are responsible for your sexual behavior,” read one. “There is help! Don’t become an offender!”

The campaign generated extensive media attention. More than 200 stories appeared in domestic and international print media alone. Beier was invited onto popular talk shows across the country, sometimes in contentious segments that paired him against the victims of sexual abuse. “It was not fun,” he says, dryly. “At the beginning, it was not easy.” When Dunkelfeld’s offices officially opened in June 2005 at the Institute of Sexology and Sexual Medicine at Charité, a university hospital in Berlin, protestors camped outside, carrying signs about how pedophiles shouldn’t be normalized — they should be executed.

But all the attention brought in many patients. In the first three years, 808 people contacted Dunkelfeld’s offices asking for help. They called from Berlin, from elsewhere in Germany, and from Austria, Switzerland, and England to see if they qualified for treatment, which might include talk therapy and drugs like anti-depressants and testosterone blockers. To date, according to the project, Dunkelfeld has heard from potential patients from 40 countries; as of June 2019, more than 11,000 individuals had contacted Dunkelfeld for help and 1,099 were treated.

The spotlight also enabled Beier to explain his approach, which he says originally was sometimes misunderstood. On television shows and in media reports, Beier came armed with a medical degree, a doctorate in philosophy, clinical detachment, and political savviness. He explained his theories to a national audience willing to hear them. “Our philosophy is that this is part of human sexuality,” he says. “And we always said that they should never act out on their fantasies.”

Beier has what he calls a “clear standpoint” regarding sexual attractions toward children: He separates desires from actions. Beier wants men to accept their sexuality so that they can control it. But if and when fantasies about boys and girls progress into reality, they become child rape, among the most heinous crimes imaginable. “This is the core idea of prevention,” he says. “We condemn behavior.”

Beier’s public-relations skills led to more support, as well as more access for potential patients. In an email to Undark, Beate Wild, a media relations officer for the Federal Ministry of Family Affairs, wrote that the State of Berlin provided interim financing for Dunkelfeld in 2017. The following year, the costs began being largely covered through health insurance. Today, with therapy locations throughout Germany, Beier says that he receives inquiries from men all over the world — including Americans. The German government will not fund treatment for non-Germans, however. As a result, some men have funded their own treatment — about $9,000 annually, not including travel and other expenses — out-of-pocket. Some men who can’t afford to move to Germany receive virtual therapy through a secure program that offers end-to-end encryption. Because it is covered by public insurance, Beier believes the project now has long-term sustainability.

Spreading aspects of it to even more countries, he argues, would reach more patients.

Beier has published numerous peer-reviewed articles supporting Dunkelfeld’s effectiveness. A 2009 paper, for instance, showed that more than 200 men volunteered to be assessed by the project, which proved that potential offenders of child sexual abuse “may be reached for primary prevention via a media campaign.” In a study published online in 2014, Beier presented results showing that, after receiving treatment, the patients reported improvements in psychological areas such as empathy and emotional coping, “thereby indicating an increase in sexual self-regulation.”

But Beier’s critics find the science lacking. Some researchers in Germany, for example, say that the data Beier has published just don’t support his bold claims. “After 10 years, I think it would have been nice to present some data which are really convincing,” says Rainer Banse, a psychologist at the University of Bonn. While he says he finds the work admirable, Banse adds that Beier’s ability to assess Dunkelfeld’s effectiveness is “a bit underdeveloped.”

In a 2019 paper, Banse and Andreas Mokros, a psychologist at the University of Hagen, looked at the data from Beier’s 2014 study and argued that he had misinterpreted the figures. “The data do not show that treatment within the ‘Dunkelfeld’ program leads to any reduction of the proneness to commit sexual offenses against children,” they wrote. The positive outcomes for the pedophiles’ treatment, the researchers maintained, were statistically insignificant.

Asked about Banse’s study, Beier concedes the argument. The effects were found to be insignificant in the study because the sample size was small — just 53 men. But Beier says a more comprehensive assessment is on the way, through an external analysis by psychologists at the University of Chemnitz, which should be ready by the end of 2022.

Beier says that conducting studies that meet Banse’s rigorous criteria isn’t ethical because it would require a comparison between patients who received treatment and those who did not — which would mean withholding support from some of the men, knowing that it would make them more likely to abuse children. “We’re not overpromising what we can do,” he says.

Other researchers hedged on Beier’s findings. “There is some preliminary evidence that Dunkelfeld could reduce offense risk,” Craig Harper, a psychologist at Nottingham Trent University, wrote to Undark in an email, “but the jury is still out in terms of definitive conclusions.” And Alexander Schmidt, a psychologist who studies men attracted to children and teenagers at Germany’s Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz, agrees that the work is inconclusive. In April 2019, the Swiss government gave Schmidt a grant to write an overview of Dunkelfeld’s effectiveness and make recommendations about potentially introducing similar programs in Switzerland. “In a nutshell, we told them that from a scientific point of view, we don’t know whether these programs actually are effective,” he says.

Despite the hedging, Harper has pushed back on some of the deeper criticisms of Beier’s work. In January 2020, Harper and two colleagues from Nottingham Trent University and Bishop Grosseteste University, respectively, published a paper in Archives of Sexual Behavior arguing that Banse’s study was too narrow. The stigma that pedophiles internalize, they wrote, is deeply harmful — a fact that Banse’s paper overlooked. That stigma “can lead to social isolation that can indirectly serve to increase their risk of engaging in sexual offending,” Harper wrote in an email. A program like Dunkelfeld, staffed by professionals who are trained to work with these patients, he adds,” is definitely an improvement to the status quo of waiting to treat people in judicial settings after an offense has taken place.”

Even Dunkelfeld’s skeptics praise some aspects of the program. When it comes to pedophiles, “many of them suffer a lot,” says Banse. These people are widely despised, even by psychotherapists, and Dunkelfeld offers them help. “I think from a psychological standpoint, that is absolutely laudable and worthwhile to do,” Banse adds. Harper agrees, pointing out the effect for the greater good: “Any service that assists in helping people to develop effective coping and self-regulation strategies is likely to have a positive net effect on public safety.”

And Schmidt says programs like Dunkelfeld may be beneficial as a mental health intervention. “Maybe these kinds of treatments will be working on a clinical level,” he adds, “basically, reducing stress, increasing well-being, like traditional psychotherapy. And this would be probably worthwhile to implement on its own.”

Effectiveness aside, Dunkelfeld is able to function in Germany because of the country’s lack of mandatory reporting laws. But members of German law enforcement have mixed feelings about those laws. Some have been supportive from the outset. “They are not against it because they learn from it,” Christian Pfeiffer, former director of the Criminological Research Institute of Lower Saxony, told Undark. Police “want to know more about the real crime statistics,” he added, which gives them a clearer picture of just how widespread child sexual abuse actually is. Dunkelfeld helps provide those numbers by soliciting confessions from men who have raped children or used child pornography but remain undetected by police.

Others are less sure. They “do not really understand how it is possible that there are some men out there who commit offenses that are not brought to justice,” Gunda Wössner, a criminologist at the Max Planck Institute for the Study of Crime, Security, and Law wrote to Undark by email. (The Federal Criminal Police Office of Germany declined to comment for this story and the International Criminal Police Organization did not respond to requests for comment.)

Wössner describes herself as “very ambivalent” about Germany’s laws on mandatory reporting. She says that enabling men to receive treatment before they commit a crime “is generally speaking a sign of progress.” Through her work, she has interviewed men who attempted to receive therapy for their attractions to children but were turned away by unhelpful clinicians who didn’t want to treat them — two of the men, according to Wössner, later committed crimes against children. But she cautions that Dunkelfeld’s group therapy sessions could lead some pedophiles to rationalize their behavior.

Beier pushes back on this. While some pedophiles may seek to normalize their behavior and others don’t want to be caught, the men who are open to treatment at Dunkelfeld “are motivated to stop any behavior,” says Beier. Other researchers agree that there is a distinction between people who have abused children and those who have sexual interest in children but have not offended. “People who haven’t offended sometimes take great offense at the suggestion that that they will,” says Elizabeth Letourneau, director of the Moore Center at Johns Hopkins, a program that is trying some preventative approaches in the U.S. If nothing else, she adds, Dunkelfeld “shows that tens of thousands of people want help.”

Beier spent decades working with men attracted to children under uniquely strong German patient-doctor confidentiality laws, which inspired Project Dunkelfeld. But the project is only able to function in its current form because of the country’s lack of mandatory reporting laws.

This perspective was echoed by a patient who staff at Dunkelfeld presented to Undark as a program participant. (The magazine communicated with the patient, identified only as F, via encrypted text messaging, but his identity and the veracity of his statements could not be independently verified given the anonymity of the Dunkelfeld system.) F described himself as about 25 years of age and living near Berlin, and says he approached the Dunkelfeld project after seeing it portrayed in a documentary news program. When F was 17, he says he started fantasizing about young girls. “First, it seemed harmless, as it was clear to me from the start that this was fantasy-only stuff,” he told Undark. Once he read the vitriol online directed at pedophiles, however, he became uneasy about his thoughts. “I didn’t want to do anything wrong, so I went to look for help,” he says. He contacted Dunkelfeld and began working with them a little more than two years ago.

F participates in group therapy with other pedophiles around his age, men who have never touched a child and want to keep it that way. He says he’s found the therapy extremely helpful. He’s put together a “protection plan consisting of all factors that help me to only ever do legal and morally acceptable things,” he says. For instance, he knows that his mother was abused as a child, and he always reminds himself that he wants to be a better person than the man who assaulted her. Similarly, he abstains from alcohol and cannabis. “It works for me, and in fact, it’s more than I would strictly need” he says. “I just like to be extra safe.”

For F, the absence of mandatory reporting laws was irrelevant — he’s never harmed anyone. However, he says that Dunkelfeld therapists told his group that if any of them said they planned to abuse a child or adolescent, they would be reported to authorities.

F maintains that some pedophiles like him can control their urges and shouldn’t have to be ashamed of their natural inclinations. “Your sexual desires don’t define who you are ethically,” he says.

“Don’t judge a person because of what they feel,” he adds, but rather “judge them for what they do.”

In the U.S., strict mandatory reporting laws, among other things, make it more difficult to formulate a preventative approach, let alone one on the scale of Dunkelfeld. “What is going in Germany with the laws and the access to treatment that folks have is just so different from what’s going on in the United States,” says Amanda Ruzicka, director of research operations at the Moore Center.

Experts point to the benefits of the laws, such as making the public more aware of the problem to begin with. “I think mandatory reporting laws in the American context have a lot of benefits,” says Ryan Shields, a criminologist at the University of Massachusetts Lowell. In particular, they “have been part of, I think, a suite of responses that have elevated knowledge about child sexual abuse, and the ways we talk about child sexual abuse, and respond to child sexual abuse.” As part of this raised awareness, the public generally continues to support mandatory reporting laws — and punishment, which Ruzicka calls a “They’re-a-monster-lock-them-up mentality.”

Still, at least among some U.S. experts, there is skepticism of mandatory reporting and a broader push away from pure punishment. “Mandatory reporting has unintended consequences,” says Berlin of the National Institute for the Study, Prevention, and Treatment of Sexual Trauma. “A law designed to help people actually drives people underground.” Shields agrees, pointing out that some people who have never harmed a child or looked at sexual images of children believe that they will be reported to authorities if they confess to, for example, having dreams about minors.

For researchers in the U.S. and elsewhere, Dunkelfeld can offer inspiration and ideas about what a prevention-first approach might look like, if not a directly applicable model. “We know what their mission is, and it’s very similar to ours,” says Ruzicka. “We’re both looking to prevent child sexual abuse.”

Around 2011, Letourneau heard Beier speak and “the lightbulb went off,” she says, to create a U.S.-based program aimed at young people, who are still understanding their sexuality and are more sympathetic to critics than older adults who are attracted to children. In theory, without intervention, these juveniles may grow up to be adults who act on their urges; by reaching them while they are still young, Letourneau and her team might prevent abuse. Several times in the ensuing years, Beier met with Letourneau to see how such a program might work.

While Letourneau says Beier had no impact on the Moore Center’s founding in 2012, he did help inform Help Wanted, which the center launched in May 2020. It’s aimed at adolescents and young adults who may be predisposed to pedophilia. In addition to a website offering an educational course and other resources, Help Wanted consists of an ongoing study of adults who have assisted young people struggling with these attractions. To date, more than 180,000 users have visited the Help Wanted homepage.

“We started talking with just folks in general who have this attraction, and a lot of them started to tell us that it was a slow realization that they had, just like we all start to realize what we’re sexually attracted to in our adolescence and young adulthood,” says Ruzicka. They created the site for “anybody who is out there looking for information on an attraction to pre-pubescent children.”

The Moore Center understands the delicacy of the issue, however. “Our approach with ‘Help Wanted’ has been, we don’t have direct contact between treatment staff or researchers, and clients,” says Shields, who previously worked at the Moore Center. The work is done anonymously and confidentially so anyone can access it. “There’s no sort of direct interaction where reportable things would be transmitted. We’ve kind of taken a strategy of working with the restrictions that we have.” Last year, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention awarded a $1.6 million grant to Help Wanted. The researchers will use the funds to evaluate the effectiveness of Help Wanted, which will then be used to revise the program. The grant will also help researchers examine risk factors — such as substance misuse — that may influence an individual to act on their attraction and molest a child.

The Institute of Sexology and Sexual Medicine at Charité also oversees a website and self-help program called “Troubled Desire,” based on experience from Project Dunkelfeld, that can connect users to resources in their respective countries.

Compared to Dunkelfeld’s size and scale, the funding for Help Wanted isn’t much. But Letourneau and others argue that it is an important start, particularly in a country like the U.S., which so heavily leans toward severe punishment of sex crimes. Using publicly available data from state and federal records, she found that the country spends $5.25 billion annually just on incarcerating people convicted of sexual offenses involving children, a figure which doesn’t include pre-incarceration or post-release costs. “What if we put some of those resources toward prevention?” she asks. “So a kid doesn’t have to be abused before we intervene.”

About The Author

Jordan Michael Smith has written for the New York Times, Washington Post, The Atlantic, and many other publications.

This story has been supported by the Solutions Journalism Network, a nonprofit organization dedicated to rigorous and compelling reporting about responses to social problems.

This article orginally appeared on Undark