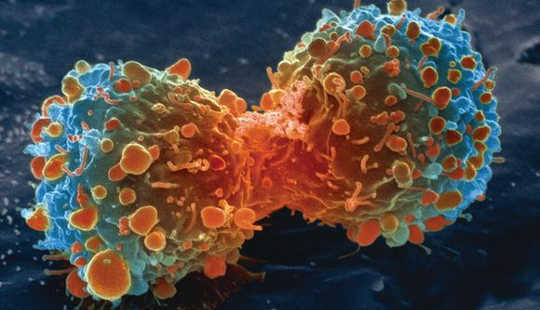

Cancer cells are survival artists with a strong criminal streak. They surround themselves with a protective shield of extra-cellular material and then secure supply lines by attracting new blood vessels.

To achieve both of these aims, they set immune cells a honey trap by releasing attractants in the form of messenger molecules which lure immune cells to growing tumours. At the cancer site, the abducted immune cells release growth hormones to guide new blood vessels to the tumour and help build a protective shield.

Since immune cells are hard to come by, cancer cells benefit from sites of chronic inflammation or larger wounds in their close vicinity as both attract them. This explains why up to 20% of cancers are linked to chronic inflammation. Two associations include chronic inflammation of the liver or the bacterial infection of the stomach by Heliobacter pylori. How cancer cells pull off this trick is, however, largely unknown.

A Social Network

A fascinating insight into the intricate social network of cancer cells has just been published in The EMBO Journal. Two British research teams based in Bristol and Edinburgh, and one Danish team based in Aarhus, report that pre-cancerous cells redirect immune cells from nearby wounds to help them grow. Cancer cells mimic the signals, which are normally released at sites of tissue damage, to pinch neutrophils from inflamed wounds. Neutrophils are the most abundant (40% to 75%) type of immune cells and the first-responders at sites of tissue damage.

Get The Latest By Email

Nicole Antonio, Marie Bønnelykke-Behrndtz and Laura Ward took advantage of the translucent stage of young zebrafish (a model organism in animal research) to capture videos of moving neutrophiles. To initiate this movement they induced clones of cancerous cells to grow in the zebrafish and then inflicted laser wounds adjacent to them. In the absence of cancer cells, the rapidly recruited neutrophils remained for up to four hours at the damaged site. However in the presence of cancer cells, they became distracted from the wound and visited the nearby clones.

The team also provided evidence for a direct interaction between the abducted neutrophils and the malignant cells. During their “chat”, which lasted up to 90 minutes, the immune cells released a chemical known as prostaglandin E2 to stimulate growth of the nearby cancer colonies.

What Of Human Risk

Their ground-breaking work raises, of course, the important question of whether human cancer cells pull off the same dirty trick.

It has already been established that the ulceration of melanoma, the rarest but most deadliest form of skin cancer, is a bad prognostic indicator. So the teams then analysed human melanoma samples taken from patients with different degrees of ulceration. They found a 15-fold increase in neutrophils from samples taken from non-inflamed melanomas to moderately ulcerated lesions, and a 100-fold increase from non-inflamed to excessively ulcerated lesions.

This shows that some human cancer cells share the ability to abduct and misuse immune cells to their advantage. It also poses the question of whether cancer surgery could enable malignant cells to survive when wounds become inflamed. A recent analysis of breast cancer operations indeed suggested that the use of anti-inflammatory drugs such as ketorolac given to patients before and after surgery leads to a lower recurrence of their breast tumours. Their exciting findings may also explain why aspirin, which blocks the production of prostaglandin E2 so efficiently, reduces the risk of developing several types of cancer.

The new observations could pave the way for new anti-cancer therapies if it were to be possible to turn the abducted neutrophils into a trojan horse which would kill pre-malignant cells. The high impact of their work illustrates also the power of international collaborations which are much more powerful than the sum of of individual contribution in science and cancer research.

About The Author

Thomas Caspari is Reader in Cancer Biology at Bangor University. His research group tries to find an answer to this question by studying how our genetic information changes over time. Many of the key events which alter our DNA occur when cells copy their chromosomes. During this process the DNA must be opened up making it vulnerable to breakage and chemical modifications.

Thomas Caspari is Reader in Cancer Biology at Bangor University. His research group tries to find an answer to this question by studying how our genetic information changes over time. Many of the key events which alter our DNA occur when cells copy their chromosomes. During this process the DNA must be opened up making it vulnerable to breakage and chemical modifications.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.