Nearly one in three low-income people who enrolled in Michigan’s expanded Medicaid program discovered they had a chronic illness that had never been diagnosed before, according to a new study.

And whether it was a newly found condition or one they’d known about before, half of Medicaid expansion enrollees with chronic conditions said their overall health improved after one year of coverage or more. Nearly as many said their mental health had improved.

Care now or complications later

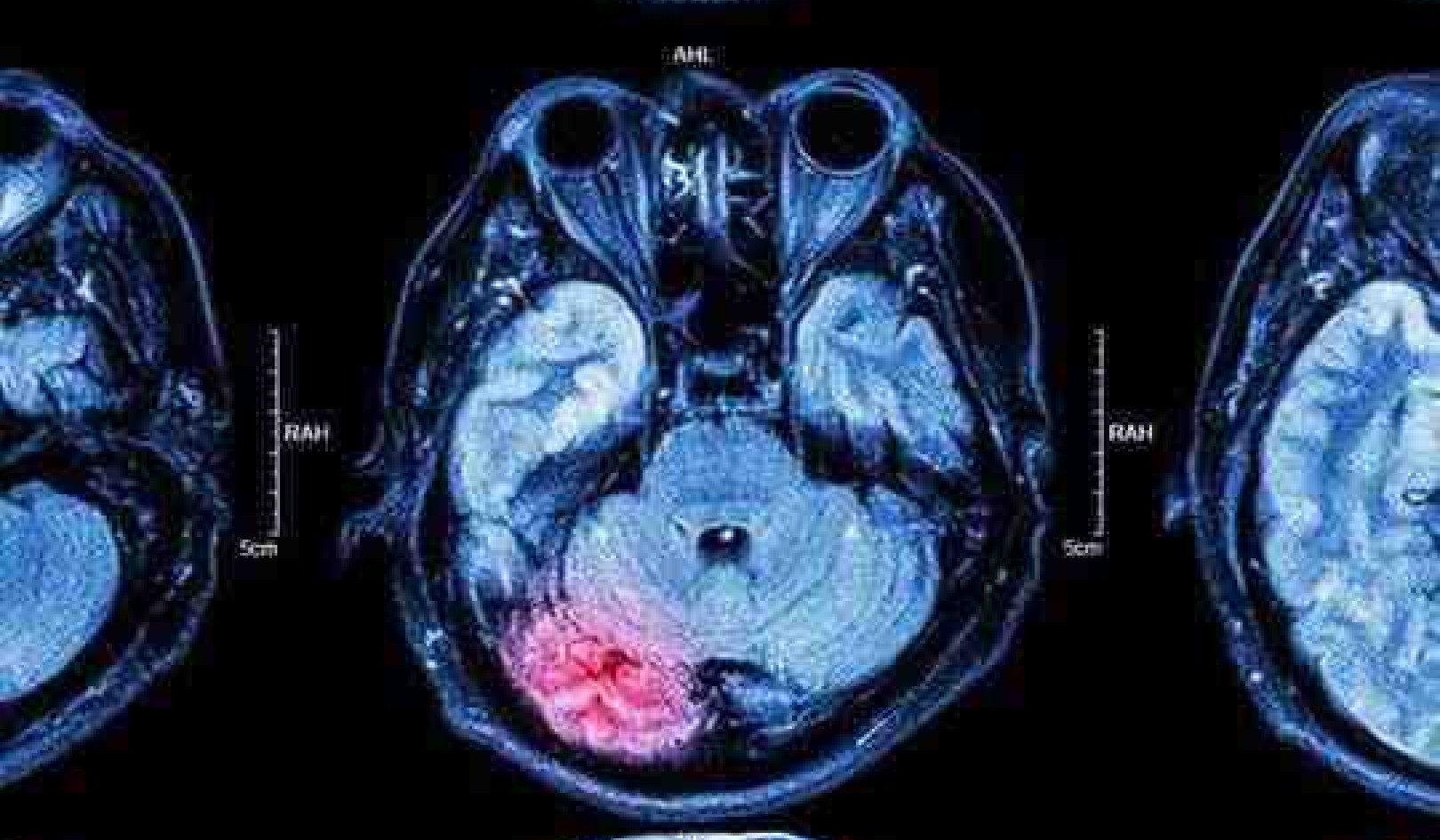

The study looked at common chronic diagnoses such as diabetes, high blood pressure, depression, and asthma—the kinds of conditions that can worsen over time if not found and treated. Left untreated or under-treated for years, they can heighten risks for costly health crises such as heart attack, stroke, kidney failure, blindness, and suicide.

A team from the University of Michigan Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation used surveys and interviews with people enrolled in the Healthy Michigan Plan, which extended health insurance coverage to adults living near or below the poverty line. Their findings appear in the Journal of General Internal Medicine.

Get The Latest By Email

The findings suggest that low-income people enrolled in expanded Medicaid are now getting care that could prevent complications later in life. The interviews reveal that many knew they should be getting such care but couldn’t afford it.

Notes for more Medicaid expansion

The findings also point to an important message for states that have recently expanded Medicaid or are considering it, says lead author Ann-Marie Rosland.

“New Medicaid expansion programs will need to be prepared to provide a large amount of care for newly diagnosed or untreated chronic conditions,” says Rosland, a former University of Michigan researcher now at the University of Pittsburgh. “But a focus on care for people with chronic conditions is particularly likely to lead to improvements in enrollees’ health.”

Rosland worked with Susan D. Goold and other members of the IHPI team that is carrying out an official evaluation of the Healthy Michigan Plan.

“Michigan’s Medicaid expansion emphasizes primary care and health risk assessment, and many enrollees were found to have a chronic condition that will benefit from ongoing management,” says Goold, a professor of internal medicine at the University of Michigan.

“Soon after enrollment, those with chronic conditions reported substantial improvements in access to care and in health compared to before they got Healthy Michigan Plan coverage. Improvements in access and health could well lead to improved quality of life and ability to work and care for family.”

New diagnoses

The researchers tallied data from a representative sample of 4,090 people who had been covered by the Healthy Michigan Plan for at least a year, and compared them with a similar population of Michigan residents. They also conducted in-depth interviews with a diverse group of 67 people who had been enrolled in the program at least six months.

In all, 68% of those surveyed had at least one chronic health condition, 58% had two or more, and 12% had four or more. Of those with a chronic condition of any kind, 42% said it had been identified after their enrollment.

The researchers found that more than a third of those with diabetes or serious chronic lung disease said it had been diagnosed since they enrolled. So had one-third of those who said they had high blood pressure or heart disease, and nearly a third of those with depression, anxiety, or bipolar disorder.

Two-thirds of those who said their condition was newly diagnosed had been uninsured in the year before they enrolled.

Those with chronic conditions were more likely to be white and have very low incomes, less than one-third the federal poverty level. In the year of the study, the poverty level was an annual income of $11,880 for an individual, and individuals making up to $16,394 qualified for Healthy Michigan Plan.

Knowing about a diagnosis is only the first step in managing a chronic condition, the researchers note.

Getting access to appointments with health providers, medicines, and other treatments and support services is also important. Two-thirds of those with chronic conditions said their access to prescription drugs had improved. Within a year of enrolling, 90% had seen a primary care physician.

‘You’re not afraid to go to the doctor.’

While studies of other states’ expansion programs haven’t found signs of improved health and access to care until two to four years after Medicaid expansion, the new study found signs that this was already happening over an even shorter time period in Michigan.

In all, 52% of those with chronic conditions said their physical health had improved, and 43% said their mental health had improved. After the researchers adjusted for other health and demographic factors, those with chronic conditions were nearly twice as likely as other Healthy Michigan Plan participants to say that both types of health had improved.

“For the enrollees with chronic conditions, we were particularly struck that people who reported they had better access to mental health care said their physical health improved more often,” says Rosland. “This was in addition to health improvements linked to things like better prescription and primary care access.”

The interviews with enrollees also yielded interesting findings. Said one man, “I had diabetes for 7 years… I just ignored it because I couldn’t afford the medicine… I got my diabetes under control and I feel a lot better.” And one woman told the researchers that after enrolling, “You’re not afraid to go to the doctor. So you take care of these situations before they get too bad.”

IHPI’s evaluation of the Healthy Michigan Plan, as required by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, receiving funding via a contract with the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services.

Source: University of Michigan

books_healthcare