Half the participants were asked to eat more vegetables, legumes, fruits, nuts, olive oil, and fish – and less red meat and dairy. stockcreations/ Shutterstock

Half the participants were asked to eat more vegetables, legumes, fruits, nuts, olive oil, and fish – and less red meat and dairy. stockcreations/ Shutterstock

As our global population is projected to live longer than ever before, it’s important that we find ways of helping people live healthier for longer. Exercise and diet are often cited as the best ways of maintaining good health well into our twilight years. But recently, research has also started to look at the role our gut – specifically our microbiome – plays in how we age.

Our latest study has found that eating a Mediterranean diet causes microbiome changes linked to improvements in cognitive function and memory, immunity and bone strength.

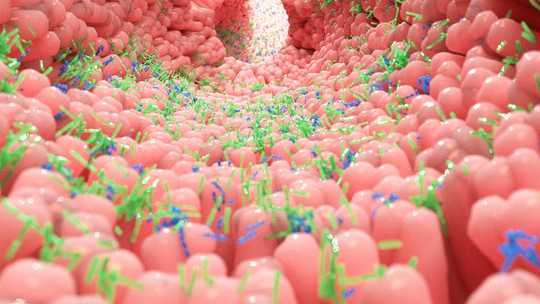

The gut microbiome is a complex community of trillions of microbes that live semi-permanently in the intestines. These microbes have co-evolved with humans and other animals to break down dietary ingredients such as inulin, arabinoxylan and resistant starch, that the person can’t digest. They also help prevent disease-causing bacteria from growing.

However, the gut microbiome is extremely sensitive, and many things including diet, the medications you take, your genetics, and even conditions like inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome, can all change the gut microbiota community. The gut microbiota plays a such a huge role in our body, it’s even linked to behavioural changes, including anxiety and depression. But as for other microbiome-related diseases such as type 2 diabetes and obesity, changes in the microbiome are only part of the issue – the person’s genetics and bad lifestyle are major contributing factors.

Get The Latest By Email

Since our everyday diets have such a big affect on the gut microbiome, our team was curious to see if it can be used to promote healthy ageing. We looked at a total of 612 people aged 65-79, from the UK, France, the Netherlands, Italy and Poland. We asked half of them to change their normal diet to a Mediterranean diet for a full year. This involved eating more vegetables, legumes, fruits, nuts, olive oil and fish, and eating less red meat, dairy products and saturated fats. The other half of participants stuck to their usual diet.

Mediterranean microbiome

We initially found that those who followed the Mediterranean diet had better cognitive function and memory, less inflammation, and better bone strength. However, what we really wanted to know was whether or not the microbiome was involved in these changes.

Interestingly, but not surprisingly, a person’s baseline microbiome (the species and number of microbes they had living in their gut before the study started) varied by country. This baseline microbiome is likely a reflection of the diet they usually ate, alongside where they lived. We found that participants who followed the Mediterranean diet had a small but insignificant change in their microbiome diversity – meaning there was only a slight increase in the overall number and variety of species present.

However, when we compared how strictly a person followed the diet with their baseline microbiome data and their microbiome after following the diet, we were able to identify two different gut microbe groups: diet-positive microbes that increased on the Mediterranean diet, and diet-negative microbes whose abundance was reduced while following the diet.

Diet-positive microbes are microbes that flourished in the Mediterranean diet. Diet-negative microbes either couldn’t metabolise the diet, or they were were unable to compete with diet-positive microbes. These diet-positive microbes were linked with less frailty and inflammation in the body, and higher levels of cognitive function. Losing the diet-negative microbes was also associated with the same health improvements.

Those who followed the Mediterranean diet had more healthy microbes in their gut. Alpha Tauri 3D Graphics/ Shutterstock

Those who followed the Mediterranean diet had more healthy microbes in their gut. Alpha Tauri 3D Graphics/ Shutterstock

When we compared the changes in the number of these microbes in the treatment group (those on the Mediterranean diet) and the control group (those following their regular diet), we saw that the people who strictly followed the Mediterranean diet increased these diet-positive microbes. Although the changes were small, these finding were consistent across all five countries – and small changes in one year can make for big effects in the longer term.

Many of the participants were also pre-frail (meaning their bone strength and density would start decreasing) at the beginning of the study. We found the group who followed their regular diet became frailer over the course of the one-year study. However, those that followed the Mediterranean diet were less frail.

The link between frailty, inflammation, and cognitive function, to changes in the microbiome was stronger than the link between these measures and dietary changes. This suggests that the diet alone wasn’t enough to improve these three markers. Rather, the microbiome had to change too – and the diet caused these changes to the microbiome.

These types of studies are challenging and expensive, and the microbiome dataset is often difficult to analyse because there are many more data-points to study than there are people in the study. Our findings here were possible because of the large group sizes, and the length of the intervention.

However, we recognise that following a Mediterranean diet isn’t necessarily doable for everybody who starts thinking about ageing, usually around the age of 50. Future studies will need to focus on what key ingredients in a Mediterranean diet were responsible for these positive microbiome changes. But in the meantime, it’s clear that the more you can stick to a Mediterranean diet, the higher your levels of good bacteria linked to healthy ageing will be.

About the Author

Paul O'Toole, Professor of Microbial Genomics, School of Microbiology and APC Microbiome Institute, University College Cork

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

books_nutrition