The desert raisin is a member of Australia’s native bush tomato family.

The desert raisin is a member of Australia’s native bush tomato family.

The species Solanum centrale, also known as kutjera in several Aboriginal languages, or the desert raisin in English, stands out in Australia’s wild bush tomato family in more ways than one.

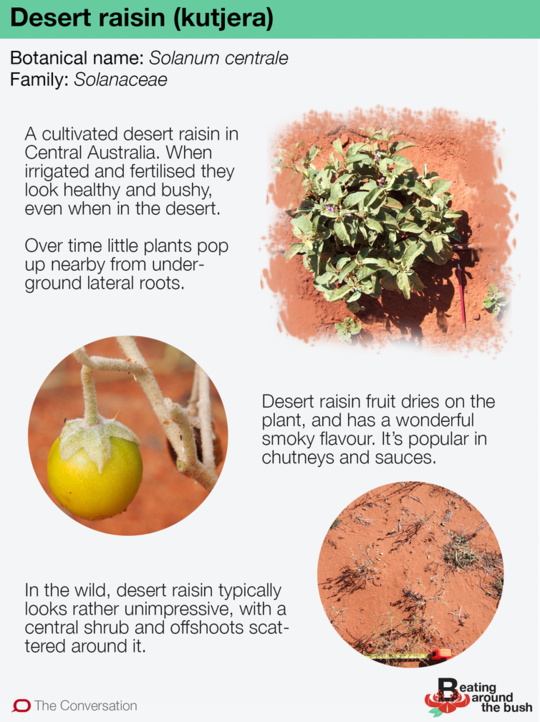

A typical desert raisin plant in the wild looks fairly unimpressive from the surface, and certainly a lot less striking than the photos which pop up in an internet search.

In fact, if you don’t know what you are looking for, you may miss them. They are fairly scrawny with greeny-grey hairy leaves and grow no taller than to the bottom of your shin.

You might only spot a shoot every few metres between other shrubs. Each shoot only has a handful of leaves, and it typically carries three to 10 sultana-sized fruit. Like sultanas, they’re unappealingly brown and shrivelled. And you’ll only see them if they have escaped hungry desert fauna.

Get The Latest By Email

But its humble appearance belies its significance to both people and the environment.

The fruit from this plant has been a staple in desert communities for thousands of years. It resembles a raisin but tastes like a piquant or smoky sun-dried tomato, and because it dries on the plant it has a long storage life relative to other fruit.

Its cultural significance and ability to grow in sandy arid areas where almost no other domesticated plants survive makes this species a prime target for an enterprise based in remote Aboriginal communities, producing a unique fruit with plenty of health benefits to consumers.

The Conversation

The Conversation

What makes the desert raisin unique?

Iceberg-like growth

Like an iceberg which is much bigger under the surface than appears from above, the desert raisin plant is much bigger under the surface of the ground than it appears. A single plant in the wild can span dozens of metres through hardy underground connections. The largest confirmed single plant was about one quarter of a hectare – but who knows how big these plants can really grow?

It expands in multiple directions from the seed plant over successive rains via roots which grow roughly parallel to the surface, producing new shoots as it expands.

Root sprouting allows a plant to grow a new shoot many metres away from the previous shoot while avoiding a vulnerable seedling stage. This feature is common among many unrelated desert plant families.

For example, a single Populus euphratica tree in the hyper-arid Taklamakan Desert of China was found to produce clonal shoots over an area of 121ha.

Unabated resilience

Desert raisins are known to grow vigorously following a disturbance, either natural or man-made. It is quite common, for instance, when driving through Australia’s arid interior to find piles of sand beside freshly graded roads covered in bush tomato shoots after rain.

Read more: The black wattle is a boon for Australians (and a pest everywhere else)

This is because a grader, a tool that smooths the surface of a road, cuts dormant roots and throws them, mixed with sand, onto the side of the road. The roots are ready to re-sprout as soon as they get wet.

And its not only chopping roots that appears to stimulate growth – targeted fires, fruit collection by Indigenous groups and grazing by desert marsupials have all been known to increase the vigour of patches of wild bush tomatoes over the long term.

The traditional custodians of this country knew how to manage this species for sustainable production, and people from Aboriginal nations which span the large range of edible bush tomato species have passed this knowledge down for centuries.

Cultivation

Do the unique root properties of the desert raisin remind you of a weed?

Well, yes.

When cultivated, desert raisin plants are large and thick, sometimes as high as the knee, with dozens of flowers per plant. Wikimedia, CC BY

When cultivated, desert raisin plants are large and thick, sometimes as high as the knee, with dozens of flowers per plant. Wikimedia, CC BY

Other root sprouters in the Solanum family from temperate areas are vigourous weeds in cropping regions around the world.

Colonies are very difficult to eradicate as the viability of roots is not affected by cultivation and most herbicides. In fact, cultivation stimulates sprouting from root fragments.

So how does this influence the way this species can be used as a food crop?

There are currently several cultivated stands in regional and remote Australia, and the benefits of growing the species are becoming clearer, particularly for Aboriginal communities.

With water and nutrition in their natural habitats, bush tomatoes can become incredibly productive. When cultivated, the plants are large and thick, sometimes as high as the knee, with dozens of flowers per plant. But over the seasons they respond less to water and fertiliser.

It is at this point that perhaps a disturbance can be used to stimulate production from underground lateral roots – although if they pop up in the space between beds, it can create havoc for other operations!

It is no wonder that a plant, which normally hides its massive size so it can persist in harsh conditions, becomes a showy, vigorous plant when given the same kind of treatment as horticultural plants.

One final note. Much of the knowledge on how bush tomato and other food plants native to this country work is held by the traditional custodians of the species, the Aboriginal people.

We must all learn from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, listen, and work together so the amazing fruits of this land return to their place in human diets and landscapes, including the mighty desert raisin.

About he Author

Dr Angela Pattison, Research scientist at Plant Breeding Institute, University of Sydney, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

books_food