A few years ago, convincing meat-free “meat” was nothing more than a distant dream for most consumers. Meat substitutes in supermarkets lacked variety and quality. Plant-based burgers were few and far between in major fast food outlets – and meaty they were not.

But realistic alternatives to environmentally damaging meat are now big business – and global fast food chains are finally starting to take notice.

Burger King has announced that after a hugely successful trial, it will roll out its partnership with plant-based meat company Impossible Foods across the US. McDonalds recently introduced the similarly meaty Big Vegan TS in its outlets in Germany, one of its five largest international markets.

Now finally able to produce meat-free imitations that are for many indistinguishable from their beefy counterparts, the rapidly growing industry appears set to make serious waves in the once impregnable bastions of cheap meat. In so doing, it could kickstart a rapid decline in meat’s contribution to the climate crisis – driven not just by a global minority of vegans and vegetarians, but by millions of meat-eaters too.

Get The Latest By Email

Joining the meatless burger bandwagon

Thanks to rising interest in food technology from Silicon Valley’s start-up scene, such indistinguishable vegan meat came on the menu a little over five years ago. Helped by huge investments, sophisticated marketing, and a friendly regulatory environment, US companies leaped to the forefront of vegan meat innovation. Products such as the Impossible Burger and the Beyond Burger soon entered into many smaller US restaurants and fast food outlets, before Burger King made it widely available across the country.

In contrast, for a long time, tighter food regulations in Europe stifled meatless meat innovation. Thanks to the European Union’s precautionary principle, companies face much more stringent checks to show that new ingredients and foods aren’t harmful before they can go on sale. Quorn, a low-cost meat substitute that is now a household name, took almost ten years to be approved as a legitimate foodstuff, because its use of fungi was unprecedented.

These tight regulations also stipulate that genetically modified ingredients have to be labelled, which may explain why the widely heralded Impossible Burger – which uses genetically modified yeast to produce the blood-like plant protein that tastes so much like beef – has not yet landed in European countries.

Combined with differences in language, food culture and investment climate across European states, innovative start-ups looking to bring high-quality meat analogues took longer to thrive in Europe.

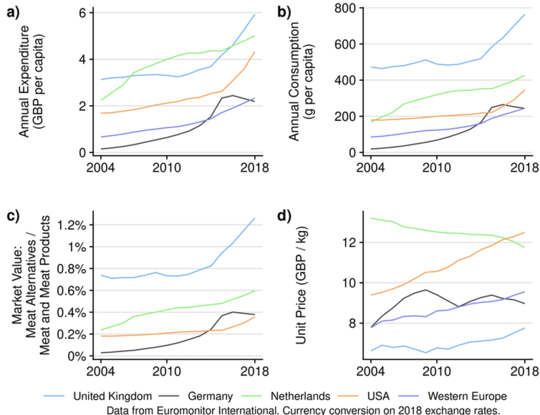

But while the US may have had a head-start in high-quality vegan meat innovation, it may surprise you to know that plant-based alternatives are much more popular in parts of Europe. While some European states such as France, Portugal and Switzerland are yet to warm to fake meat, the average Briton (750g) or Swede (725g) consumed nearly twice as many meat alternatives in 2018 as in the US (350g), where vegan meats are have typically been more realistic and thus higher-priced than in much of Europe.

With the market growing at times by orders of magnitude as traditional meat-eaters switched on to plant-based products, it was only a matter of time before major European companies started cottoning on to the potential of high-quality meat imitations.

In 2017, McDonald’s was quick to roll out a vegan burger, the McVegan, at its restaurants in Finland and Sweden. But it was not designed to closely resemble meat, and was marketed primarily at vegans.

In the UK, where more than half of British people have either already reduced or are considering reducing their meat consumption, Greggs decided to blaze the trail. Having only last year considered vegan sausage rolls “too difficult” a proposition, they are now returning record profits thanks to an offering so popular that the bakery has struggled to keep up with demand.

In traditionally meaty Germany, meat alternatives were practically non-existent ten years ago. But Germans now aren’t far off the USA in fake meat consumption, thanks in part to prominent processed meat brands entering the market. It’s no coincidence that McDonald’s in Germany has since decided to partner with Nestlé, a new major player in the meatless meat game, to offer a vegan burger there.

The market for plant-based meat is rapidly growing across Europe and the USA. Malte Roedl/Euromonitor International, Author provided

The market for plant-based meat is rapidly growing across Europe and the USA. Malte Roedl/Euromonitor International, Author provided

If news of out-of-reach vegan burgers is giving you food envy, there is no need to worry. Different cultures, tastes, prices and administrative hurdles mean that developments will not happen everywhere at the same time. But in the next couple of years, expect to see a lot more plant-based meat coming to fast food chains near you.

Realistic chicken imitations have thus far proved difficult to master, but KFC plans to trial a vegan version of its chicken fillet burger from June 17. Meanwhile Burger King is already exploring how best to bring its vegan burger to Europe.

And, given the whopping 30% increase in sales brought by the Impossible Whopper, McDonald’s and Nestlé are already considering expanding their partnership beyond Germany.

Crucially, these fast-food vegan meats are not just aimed at vegans and vegetarians, but meat-lovers too, who still make up the vast majority of the country populations across the world. The Impossible Whopper, for example, is marketed not as a planet-saving treat, but a healthier way to enjoy the same meaty taste their customers are used to.

Some vegans baulk at the idea of replicating the taste of animal flesh – but the bigger picture is that such products will play a major role in realising projections that the majority of “meat” will not come from dead animals by 2040.

Taste and health still far outweigh concern for the environment and animal welfare as factors that determine whether people are willing to purchase plant-based meat. By tapping into these, vegan meat can massively reduce the hefty emissions burden and animal suffering caused by animal agriculture.

Bring on the vegan meat revolution, I say.![]()

About The Author

Malte Rödl, Doctoral Researcher in Sustainable Consumption, University of Manchester

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

books_food